Even before the end of Ingenuity’s primary mission as a technology demonstrator, the helicopter showed that it could provide tactical and scientific scouting for the Perseverance mission. In practice, this hasn’t always been possible, but Ingenuity has indeed proven its worth on more than a few occasions over the course of the mission. As mentioned in a previous post, the team was looking forward to doing this yet again as the rover made the long ascent up the Jezero delta.

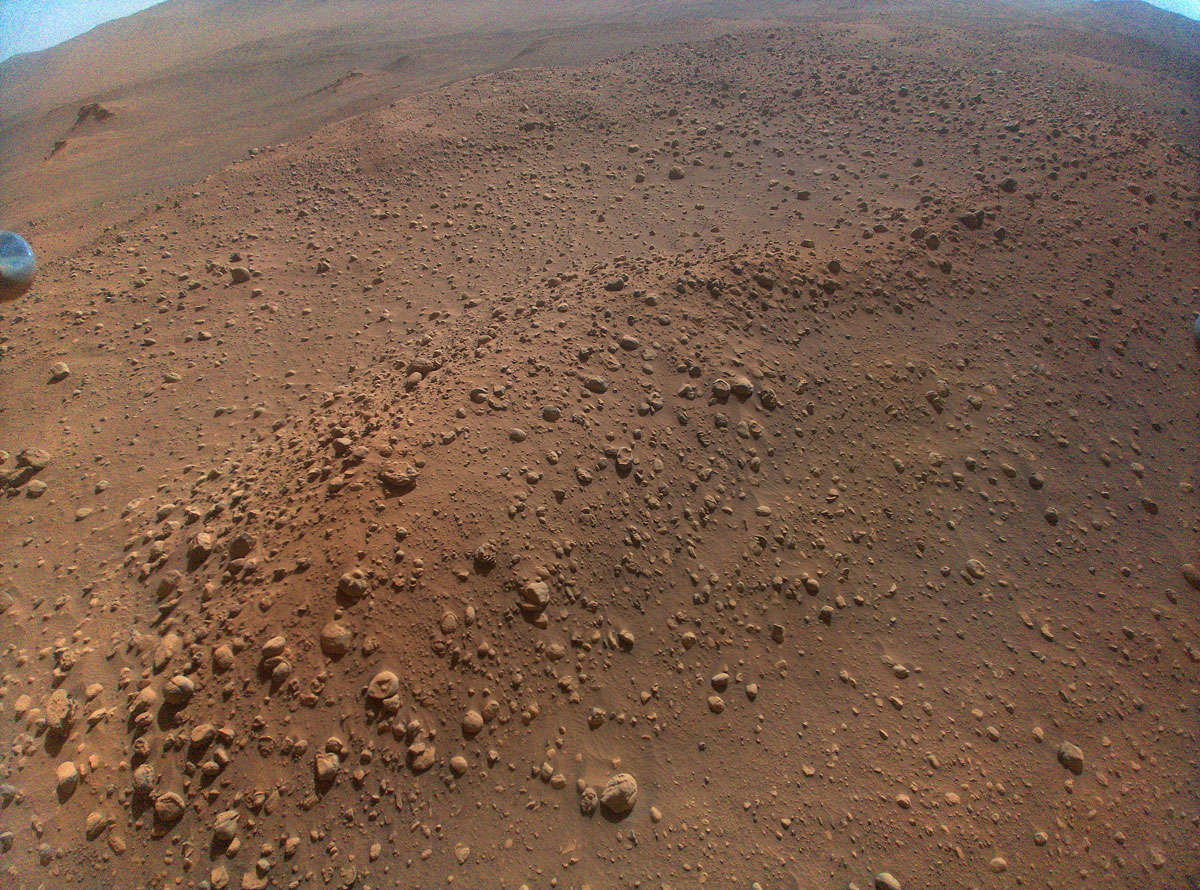

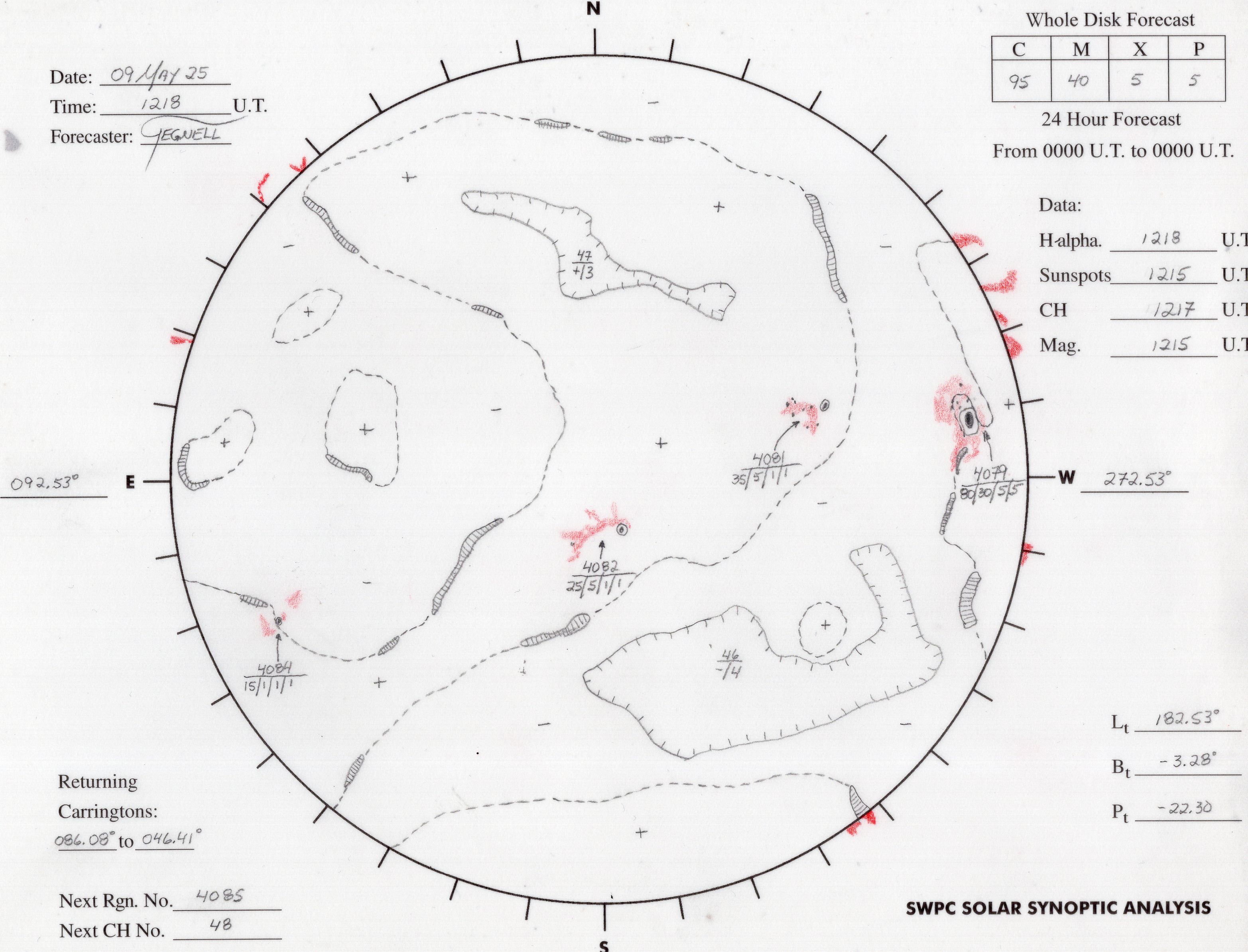

Flight 46 had put Ingenuity within sight of the scientifically important Tenby region, but a number of minor issues delayed the execution of Flight 47, allowing Perseverance to catch up to the helicopter. This precluded any close-up scouting flights of Tenby, as they would require Ingenuity to fly over the rover’s path, presenting an unacceptable risk to both vehicles. Instead, the Ingenuity team attempted to image Tenby from a distance as the helicopter moved farther up the delta on Flight 47. The field of view of Ingenuity’s Return to Earth (RTE) camera is pointed diagonally downward, capturing a relatively narrow range from slightly above the horizon to roughly 40 degrees below. This narrow field-of-view allows the camera to take beautifully detailed images of the Martian surface but leaves little room for error in targeting. Since the helicopter’s attitude (yaw, pitch, roll) naturally fluctuates in response to external factors during flight, features near the boundaries of the planned image are often left outside the actual frame. Features that are far away are invariably near the horizon, and thus close to the edge of the camera’s frame and difficult to capture reliably. This difficulty came into play on Flight 47, with the attempted Tenby scouting images just narrowly missing the main area of interest. The image the heli team was hoping to impress the rover science team with was hidden from view by just a few degrees. While these images were provided to the science team in advance of the rover’s arrival, they were unfortunately of little practical value.

The circumstances were far more favorable for Flight 48. Perseverance planned to spend at least two weeks at Tenby, followed immediately by an exploration of two other planned locations just to the west: Castell Henllys and Foel Drygarn. Scientists were understandably eager to make their plan for these regions and asked for advanced reconnaissance of Castell Henllys from the Ingenuity team. With the rover’s close proximity yielding good telecom strength, and no concerns about crossing the rover’s path, the stage was set for an ideal science scouting flight. Sure enough, Ingenuity’s 48th flight produced a treasure trove of aerial images showing the exact area of interest at a resolution several orders of magnitude better than anything prior. All of these images were downlinked to Earth and provided to rover planners and scientists a full two weeks before the rover would reach this area. For the first time since the start of the Delta Campaign, the team had found science success, setting the template for future collaboration with project scientists.

Scientists considered aerial imaging of the third science area, Foel Drygarn, to be of minimal value, so the team chose to send the helicopter farther up the delta rather than perform additional scouting flights in the region. This plan was delayed by two aborted flight attempts, the first due to high winds cooling the battery below pre-flight-check levels, and the second due to a minor command sequencing issue. On the third attempt, Ingenuity made its 49th flight on Mars. The Guidance Navigation and Control team once again managed to push the flight envelope with a 16-meter vertical popup at the end of the flight. At the peak, Ingenuity snapped the highest suborbital picture taken of the Martian surface since landing, with hopes of viewing the interior southern wall of Belva crater (something Perseverance had planned to skip due to time constraints). The team completed a transfer activity to retrieve this image (among others), but once again, the distance to the crater ensured that it remained hidden just off the top edge of the frame.

Where’s the helicopter?

That downlink was the last time the team would hear from the helicopter for an agonizingly long time. Eager to continue up the delta, the team tried and failed to uplink the instructions for Flight 50 several times. Sol after sol, the helicopter remained elusive. Each time, the downlinked telemetry from the Helicopter Base Station (HBS) on the rover would come back showing no radio sign of the helicopter.

Since the first post-winter overnight “survival” on Sol 685, the helicopter had unfortunately been drifting in and out of nighttime survival mode (having enough power to avoid overnight brownouts). As discussed in a previous post, overnight brownouts lead to uncertainty in Ingenuity’s wakeup time, which make planning much harder. The new transitional power state made morning wakeup times even more difficult to predict, with large fluctuations as the helicopter’s power state neared its overnight survival threshold. Constraints with rover power and instrument scheduling generally prevented the team from searching the entire wakeup range every morning. Unsurprisingly, the team had spent a substantial number of sols losing, searching for, and then reacquiring the helicopter over the past several weeks.

Thus, the team was not overly concerned when communication was lost with the helicopter on Sol 755. Standard practice had been to methodically search subsets of the expected wakeup window over the course of several sols, eventually building up enough coverage to catch the helicopter’s wakeup. Shortly after the missed communication on Sol 755, the rover moved to a location immediately southeast of Castell Henllys to begin a close scientific investigation of the area. This placed it in a deep communications shadow created by the rocky outcrop. As the team continued to cover the nominal search window without success, the thought that this might be a communications issue continued to assuage significant concern. When the rover emerged from the communications shadow on its way to Foel Drygarn and the helicopter was still nowhere to be found, the situation began to generate some unease. We continued widening the search windows while doing ever greater mental gymnastics to try to explain how the helicopter might plausibly wake up at those hours. Poor telecom performance was seen as a plausible explanation, but there were reasons to doubt it. In more than 700 sols operating the helicopter on Mars, not once had we ever experienced a total radio blackout. Even in the worst communications environments, we had always seen some indication of activity. This was a mental competition between two similarly unlikely and unprecedented explanations.

Finally, on Sol 761, nearly a week after our first missed check-in, our communications team observed a single, lonely radio ACK (radio acknowledgement) at 9:44 LMST (Local Mean Solar Time), exactly the time when we’d expect to see the helicopter wakeup. Another single ACK at the same time on Sol 762 confirmed that the helicopter was indeed alive, which came as a welcome relief for the team. Ultimately, this first-of-its-kind communications blackout was a result of two factors. First, the topology between the rover and the helicopter was very challenging for the radio used by Ingenuity. In addition to the aforementioned communications shadow, a moderate ridge located just to the southeast of the Flight 49 landing site separated the helicopter from the rover’s operational area. The impact of this ridge would only abate once the rover had gotten uncomfortably close to the helicopter. Second, the HBS antenna is located on the right side of the rover, low enough to the deck to see significant occlusion effects from various part of the rover.

Ready or not, here the rover comes

On Sol 762, not long after the radio ACK was received by the HBS, the rover concluded its investigation of Foel Drygarn, turned, and began an aggressive sprint up the delta. It was now closing the distance with the helicopter at full speed. This presented a serious dilemma to the helicopter team. As mentioned in previous posts, it is extremely important for Ingenuity to stay ahead of Perseverance while moving through the narrow channels of the Jezero delta. The rover was now slated to bring the helicopter inside the 45-meter no-fly zone within the next sol. Despite having not talked to the helicopter in a week, and only the knowing roughly when to expect it to wake up, the team now needed to uplink a flight or risk being passed. Relying on the helicopter’s onboard preflight checks to ensure vehicle safety and banking on solid communications from the rover’s imminent proximity, the team uplinked the flight plan. As commanded, Ingenuity woke up and executed its 50th flight on the red planet, covering over 300 meters and setting a new altitude record of 18 m. The rover had closed to a mere 80 meters by the time the helicopter lifted off in the Martian afternoon Sun. It would be an understatement to say that the helicopter team was relieved to see the successful flight telemetry in the Sol 763 downlink the following morning.

Despite the imminent return of Martian summer, it now appears that the dust covering our solar panel will ensure that Ingenuity will likely remain in this transitional power state for some time. This means that, much to the chagrin of her team, we are not yet done playing this high-stakes game of hide and seek with the playful little helicopter.

Written by Travis Brown, Chief Engineer Ingenuity Mars Helicopter at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory